When I tell people I am a writer, naturally, they ask, What have you published?

The answer isn’t long. Yet. But I’m a new writer, so I’m okay with that. For now. Because in 2010, I quit my day job as a commodity seafood buyer and sales rep. I billed myself an aspiring published writer, blogger, cook. I published a few magazine articles and like many new writers, I launched a blog. But mostly my writing sucked.

I studied, attended workshops, hired a writing coach, and mostly practiced. Ever. Single. Day. I have writing hiccups, like abusing commas, and issues with verb tense. But I’m learning. And I know a good editor can straighten me out.

Then on October 8, 2014, I received my first publishing contract.

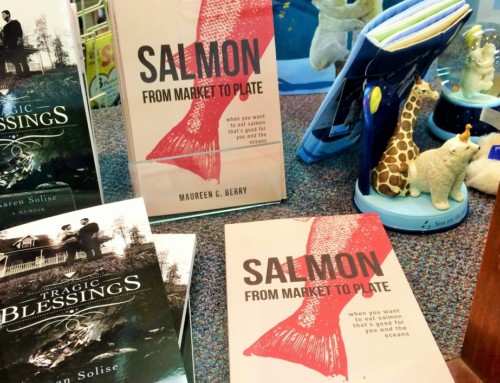

Salmon: From Market to Plate is a narrative-driven sustainable seafood cookbook, the first in a series. I received a small four-figure advance and signed my rights away. To say I was ecstatic was an understatement.

What was the chance that the first query I sent out would get the attention of an agent who said my nonfiction was “doable,” but not for her? She referred me to an agent friend at another publishing house. Its mission? To connect writers with readers who want to lead self-sustaining, self-reliant lives. My book and this publisher? A perfect fit.

I submitted the MS two months ahead of the March 8, 2015 deadline. By late spring, I was given a tentative release date, April 2016. A few months later, I was working with the editor and then a publicist.

By late summer, I was told the book would be upgraded from an illustrated black and white book to a larger, full-color photography book. The price would be higher, thus higher royalties, but the release would be pushed to October 2016.

All the while I kept thinking that this kind of thing doesn’t happen to people like me.

The insecure writer in me just didn’t want to believe that my book had found a home. Then a week or so later, my agent asked me to send five additional salmon recipes. I asked if she’d like the book proposal for the second book, Shrimp. She said yes. Three weeks later I sent the recipes and the proposal.

When I didn’t hear from her within a few weeks, I knew something was off. Call it intuition. But I knew in my gut that this contract was going sideways.

A few days later, the editor emailed—she was retiring. I’m paraphrasing here, but basically, she said, “To Paris. Life is short.”

I scheduled a call to my new editor. That’s when I was told that my project was put on hold for an indeterminate amount of time.

I didn’t cry. But I wanted to.

In a way, I felt bad for my new editor. It didn’t seem fair that she would have the burden to tell me things weren’t working out.

However, she had made a few suggestions about the direction Salmon could go. I listened eagerly, hopeful that this would still work out. She suggested that if they move the book under its “cookbook” platform that I needed to develop an additional one hundred salmon recipes. I didn’t think about that for more than a millisecond before I shot it down.

The second idea made me feel a little better. She suggested I combine all the species into one MS. While I liked this idea, and still do, I knew it would take a few years to complete the project. I told her I’d think about it over the weekend and call her the following Monday. But I knew, and she knew, that this was the end of the ride for me, Salmon, and this publisher.

The contract dissolution was amicable—my rights were reverted and I kept the advance without penalty. We agreed and hoped to do business together in the future.

***

There is no manual for emerging writers on what to expect with a first publishing contract.

Maybe there is, but I haven’t read it.

Having a publishing contract is big. Really big. Especially for someone like me, a middle-aged career changer from a seafood industry professional to a freelance writer. But if the release date is pushed further and further ahead, with no concrete end in sight, then the contract isn’t really worth anything, is it?

At first, I was crushed. Humiliated. Afraid to admit I failed. Falling on your face hurts. Especially in front of others. But then I realized that it’s not the fall that matters, it’s how you get back up.

And I know my story is not uncommon.

It’s called being a writer.