Pronounced “konk,” this large salt-water gastropod drags

itself along the seabed with the help of its big, edible muscular foot. Queen

conch, pictured here, lives inside a beautiful pink, spiral shaped shell. It is

prized for its shell and its tender meat. But poaching and over-fishing may

impact the future of conch and there is some concern, according to NOAA, that it

may become relegated to the endangered species list.

It is illegal to harvest fresh conch in the United States. Conch is harvested throughout the Caribbean, processed and frozen. It is distributed through the world in various stages, whole, chopped or ground. Conch has no bones. The entire structure of the conch is the muscle, or the foot, that lives inside the spiral shaped shell. The foot, or edible muscle,

moves this marine gastropod mollusk across the ocean floor. You can’t buy fresh conch in the U.S. but if you’re ever in the Bahamas, here are just two simple rules: buy

The first time I saw a live conch was in 1990. It also happens to be the first time I was in the Bahamas, but this story is about conch. I digress.

######

Sweet smoke filled my nostrils and it seemed like a strange backdrop to the clear-colored turquoise water that appeared to be shimmering with diamonds. The cacophony of sounds was as foreign as the terrain. Sea gulls and crows squawked to a steady beat of bongo drums. Hand slapping, clapping and a flute-like instrument of some sort filled the warm air. Men and women of various size, age and color stood side-by-side under shaded canopies of wood, tattered canvas and even a few multicolored, striped umbrellas. Their rickety stalls were a haven for hawking food, chatting and dancing. Their dark chocolate-colored skin glistened; their hands were taut, roped, and worn. White skin peeked out from the underside of their hands as they offered exotic meats, vegetables, shrimp, fish and icy, cold Kaliks, the official Bahamian beer, as if it was from the Gods themselves.

Sun-bleached wooden boats bobbed lazily along the wharf. They wore thin shredded rope, like silent, steady lovers. A steady, loud, whacking sound was coming from the boats. I peered through the crowd of big-bellied, sun-burned tourists; it sounded as though someone or something was being bludgeoned to death.

Then it was as if Moses parted the sea himself. I saw a small boy, as dark as the night, wearing long baggy shorts. His stick-like legs stuck out from his filthy shorts that looked like they’d never seen the inside of an electric washer or dryer. He couldn’t have been any older than ten and he was wielding a mallet larger than his forearm. And he knew how to use it. He slapped a pink, orange and black shape about the size of man’s hand, on a large board with the mallet, over and over. There was a pile of these pinkish-orange things, (later determined to be fresh conch) on the boat next to him. He methodically slung one after another from the pile, gave it several bone crushing blows and then tossed it into a bucket. His actions were quick and agile. It was disgusting, but a mesmerizing ordeal. A woman, presumably his mother, or older sister, came to the boat periodically to take the contents from the bucket to her stall where she chopped the conch, drizzled it with lime, sprinkled it with salt, and then scooped it into a cardboard container. Then she began her melodic chant to the sunburned tourists from the cruise ship, “Hey mista, fresh konk, fresh konk. Hey pretty lady, fresh konk, fresh konk.”

And it went like that all the way down the wharf. I didn’t dare take the bait. I was afraid. There was no refrigeration or ice, my mid-Atlantic, twenty-seven year old brain told me. It’s not sanitized. What if I get sick? It looks slimy. And on it went, my mind sloshed through a myriad of rationalizations until I moved on and away from the wharf to the next island attraction.

######

I would eat conch for the first time within the year, at a restaurant called the Cracked Conch, in Marathon, Florida. The conch was tenderized, (whacked with a mallet), battered, fried and served on a soft, egg bun and topped with a sweet, relish sauce. It was sweet and tender, and I began to crave conch and eat it in its variety of preparations: sandwiches, ceviche and fritters.

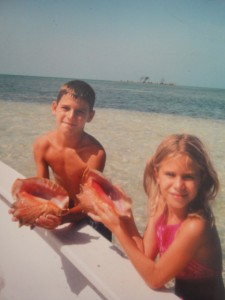

But it would be a decade until I saw live conch again. This time I was in American on the Gulf of Mexico in Marathon, Florida. Again, on vacation. Marathon had been my home for almost ten years and I was still returning to visit with my friends, Vicki and Jamie Platt, after I moved “north” to Orlando, Florida. The Platt’s had two small children, James, (whom everybody called Bucko) and Kasey. Kiley, their third and last child, would be born years later and I didn’t get the time or privilege to spend with her as I did with Bucko and Kasey.

Bucko, a fisherman by nature was driving the Platt’s 20 foot boat by this time. We loaded the boat with snorkel gear, SPF 15, two oars and a cooler of water. Our mission: paddle out to the small, uninhabited island (pictured above) off Sombrero Beach in Marathon to snorkel. After navigating through the canals to the open ocean, we found ourselves sitting on a sand bar. We hopped out of the boat into the soft, sandy bottom to push the boat out into the Gulf. Along the way, Bucko, the naturalist, discovered these two live conch’s buried in the white sand. And natural-born tourist that I am, I had Bucko and Kasey pose with the conch before we slipped them back into the safety of the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Like the Queen conch, our treasure was majestical and magical. It was like having my own two gems cradling two live conchs, sort-of like finding our own proverbial pearl in the oyster.

######

You can find Captain James Platt aboard “No Slack” Sport Fishing in Marathon, Florida. Contact Captain James to charter his award-winning charter boat.